La Danza de los Cuervos: el destino final de los detenidos desaparecidos

Javier Rebolledo

Ceibo Ediciones, 2012

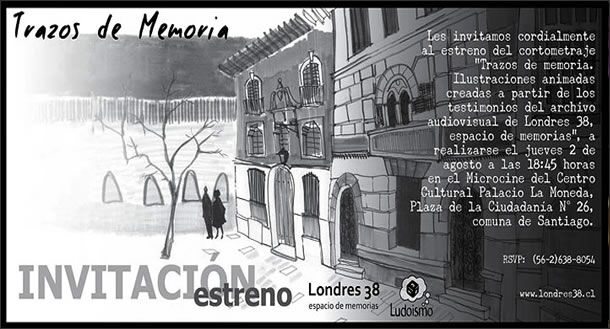

Rebolledo’s intricate research constructs the alliance between

agents of Cuartel Simón Bolívar and other detention and torture centres. A

number of agents forming part of Brigada Lautaro and Grupo Delfín were part of

the contingent from Tejas Verdes. As the persecution of MIR and Partido Comunista

militants widened to encompass all of Chile, torture centres were set up around

the country under the command of Manuel Contreras. At the time of Vergara’s

inclusion in DINA, torture centres such as Villa Grimaldi, Londres 38, Tres y

Cuatro Álamos and José Domingo Cañas were already operating under special

brigades such as Brigada Halcón, headed by Miguel Krassnoff Martchenko and

responsible for the torture of detainees at Londres 38.

Javier Rebolledo

Ceibo Ediciones, 2012

The history of Cuartel Simón Bolívar remained a heavily

shrouded secret of Direccion de Intelligencia Nacional (DINA), until the pact

of silence was broken by Jorgelino Vergara Bravo, known as ‘el Mocito’. A

struggle for survival grotesquely transformed into a life of treason – a man of

campesino origins working as a servant in the household of Manuel Contreras Sepulveda

– Head of DINA, later progressing to inclusion in DINA and transferred to

Cuartel Simón

Bolívar.

‘La Danza de los Cuervos: el destino final de los detenidos desaparecidos’

(Dance of Crows: the fate of the disappeared detainees) delves

into the atrocities committed by Brigada Lautaro and Grupo Delfín through

Vergara’s testimony who, in 2007, declared the Cuartel as ‘the only place where

no one got out alive’. Residents living

close to the extermination centre were reluctant to make friends, out of mistrust

and the uncomfortable proximity to the terror inflicted upon detainees.

Vergara’s initiation into Manuel Contreras’ realm started with his

employment as an errand boy. During the months spent at the household, Vergara

equated respect with authority, particularly manifested in his obsession with

weapon handling and ownership and learning to work in relation to crime, albeit

unconsciously at first. Contreras’ power was gradually revealed – occasional phone

calls from dictator Augusto Pinochet, the arrival of Uruguayan President Juan

María Bordaberry and the ensuing collaboration in staging Operación Condór and

Operación Colombo, the expensive automobiles, the presence of bodyguards and

the visits of other DINA agents, such as Miguel Krassnoff Martchenko, Michael Townley

and Juan Morales Salgado, were a fragment of the reality incarcerated within

Cuartel Simón Bolívar.

Javier Rebolledo portrays Vergara’s testimony as a narration of

memories, prompted by the author at times for clarification or further

information; supplemented by the author’s research through official documents

and court statements. However, it is essentially Vergara’s history intertwined

with that of the torturers and the desaparecidos of Cuartel Simón Bolívar.

Apart from his insistence that he was never involved in killing or torturing

any of the desaparecidos, the sensation of blame is effortlessly enhanced.

Indeed, Judge Victor Montiglio only acquitted Vergara on the grounds that he

was not yet an adult according to the law, during his tenure working for DINA’s

Brigada Lautaro and Grupo Delfín.

The initial realisation of betrayal is only intensified as the

book progresses. Vergara’s betrayal of his campesino origins, his betrayal of

DINA and, more importantly, the betrayal of Chile’s struggle against oblivion

merge and distance themselves incessantly. The contrasts of relieving one’s

conscience versus the convenience of acquittal, coupled with Vergara’s trepidation

of a possible assassination for revealing DINA’s profoundly fortified secret,

all point to complicity in the fate of MIR and Partido Comunista disappeared

militants.

On January 20, 2007 Jorgelino Vergara Bravo broke the pact of

silence after being falsely identified as the murderer of Víctor Manuel Díaz López,

head of the clandestine organisation of Chile’s Communist Party. Insisting that

he never killed or tortured any of the desaparecidos, Vergara’s testimony shed

light on Cuartel Simón Bolívar as Chile’s torture and extermination centre. There

had been numerous speculations about the existence of a site specifically used

for the persecution, torture and annihilation of MIR and Communist Party

Militants, but DINA refused to reveal any vital information. While Vergara was

detained in a high security prison, 74 DINA agents were immediately arrested,

leaving no chance for a possible corroboration between officials to avail

themselves of impunity. Betrayals and denials ensued. Contreras denied ever

having set eyes upon Vergara. On the contrary, Juan Morales Salgado, Head of

Brigada Lautaro, was the first to affirm that Vergara ‘was neither an

apparition nor paranoid’, confirming Vergara’s employment at Cuartel Simón Bolívar

and his previous job as errand boy in Contreras’ household.

Montiglio’s perseverance in bringing the DINA agents to justice

was abruptly terminated upon his demise from cancer in 2011. By that time,

evidence about Cuartel Simón Bolívar, the Calle Conferencia cases, as well as

the process of disappearing MIR and Communist Party militants and Operacion

Retiro de Televisores was swiftly unravelling, revealing the ruthless mechanisms

of Brigada Lautaro and Grupo Delfín.

Vergara’s previous fragmented knowledge, garnered from

conversations between Contreras and other DINA agents, including Miguel Krassnoff

Martchenko, Juan Morales Salgado, Burgos de Beer and Moren Brito, gradually

manifested itself into revelations of actual torture and extermination ritual. Serving coffee and

sandwiches to agents in the midst of torture sessions, Vergara recalls the indifference

with which instructions on how to serve coffee jarred with the sight of a

detainee writhing from excruciating torture. However, these scenes portrayed a

fragment of the torture process. Vergara’s recollections of Dr Osvaldo Pincetti

(also known as Dr Tormento) and detainees were impregnated with detail, yet the

fate of the tortured dissidents remained obscured. Dr Pincetti specialised in

hypnosis; on one occasion Vergara witnessed a victim being forced to watch

himself bleed to death – a form of torture designed to coerce the dissident

into signing false confessions or supplying information about Chilean

dissidents.

The severity of torture ensured that detainees were exterminated

and disappeared within seven days of arriving at Cuartel Simón Bolívar. Detainees

were forced to listen to their compañeros’ anguish during torture sessions

involving the parilla, which administered electric shocks to sensitive parts of

the body, including the genitals. Sometimes detainees were beaten to death or

asphyxiated. Nurse Gladys Calderon, another DINA recruit whose work experience

included assisting Dr Vittorio Orvietto Tiplizky in Villa Grimaldi and DINA

agent Ingrid Olderock, notoriously renowned for training dogs to violate women,

administered cyanide injections to all detainees. Questioned about her role,

Calderon deemed it ‘an act of humanity’ which ended the suffering of those

destined to become the desaparecidos of Cuartel Simón Bolívar.

Vergara also narrates how detainees were used to test the

manufacture of chemical weapons. Developed and manufactured by Eugenio Berriós

and Michael Townley; a US citizen recruited by DINA and now living under the

witness protection programme in the US, sarin gas featured prominently in

Cuartel Simón Bolívar. Two Peruvian men were detained and brought to the Cuartel,

where they were forced to inhale sarin gas in the presence of Contreras,

Salgado, Barriga, Lawrence and Calderon. The Peruvians were administered

electric shocks using a new device displayed by Townley and later beaten to

death. Their bodies were probably disposed of in Cuesta Barriga – the site in

question during the illegal exhumation of the desaparecidos’ bodies during

Operación Retiro de Televisores in 1979.

Memories of the torture inflicted upon Daniel Palma, Víctor Díaz,

Reinalda Pereira and Fernando Ortiz Letelier are narrated in detail by Vergara,

who describes Palma’s cries as being the loudest ever heard, prompting DINA

agents to increase the sound level of their stereos to obliterate his cries. Díaz

was tortured on the parilla, asphyxiated and later administered a cyanide

injection by Calderon, upon direct orders from Morales. After manifesting her

terror at the inability to protect her unborn child, Pereira was subjected to

mock executions and severe beatings, incited by her pleas to DINA agents to

kill her. Ortiz was beaten to death. The bodies were later subjected to further

degradation – agents pulled out the teeth in a search for gold fillings. Later,

the faces, fingers and any other particular features were torched to prevent

any possible identification. As with other Calle Conferencia victims, the

bodies of the detainees were ‘packaged’ during the night and ushered out of

Cuartel Simón Bolívar, destined for burial in Cuesta Barriga or transferred to

Pedelhue, loaded upon helicopters and dumped into the sea. According to

Vergara, the desaparecidos were deemed ‘fodder for the fish’ by DINA agents. In

1976, 80 MIR militants suffered the fate of the detenidos desaparecidos – most of

them through Cuartel Simón Bolívar.

|

| Reinalda Pereira |

|

| Víctor Díaz |

|

| Daniel Palma |

|

| Fernando Ortiz Letelier |

Vergara recalls a visit to Colonia Dignidad, run by Paul Schäfer

and notorious for its abuse against incarcerated minors. Rumours originating

from Contreras’ bodyguards indicated that DINA agents profited from the

desaparecidos by setting up an organ trafficking trade to Europe, with the

recipient countries being Switzerland and Belgium.

Betrayals ensured within DINA following its disintegration after

the assassination of Orlando Letelier. With the creation of the CNI, Vergara

was transferred to Cuartel Loyola where he found himself lacking the imaginary

protection offered by Contreras. Pressed by Rebolledo as to whether he

participated in any assassinations after his stint at DINA, Vergara replies in

a rhetorical manner, implying self-defence against aggression as implication of

participation. Rebolledo remarks upon the vagueness of Vergara’s recollections

in this period, noting once again that Montiglio had exonerated him solely because

he had been a minor during his time at Cuartel Simón Bolívar. The vague

recollections coincide with Operacion Retiro de Televisores – an encrypted

message issued by Pinochet ordering agents to illegally exhume the remains of the

bodies buried clandestinely in Cuesta Barriga. The remains were either dumped

into the sea or burned, to avoid any official investigation. Bone fragments later

discovered on site led to the identification of Fernando Ortiz Letelier, Ángel

Gabriel Guerrero, Horacio Cepeda and Lincoyán Berríos – all victims of Calle

Conferencia.

The book is punctuated with the contrast between the lives of the

desaparecidos and the agents in charge of their extermination, laying bare the

crudeness with which various sections of the Cuartel served for disparate

purposes – desaparecidos left to bleed to death in the gym, which would later

be cleaned and used by the agents for their physical training. Sporting events

were also held between different brigades of various torture centres.

Undoubtedly, Rebolledo’s research is striving to shift the

dynamics of impunity. Recently the author was subjected to acts of intimidation

when his research detailing further DINA atrocities was stolen. Chile’s

dictatorship disguised under a semblance of democracy is still resisting the

masses’ struggle in favour of memory. As

stated in the first chapters, various agents still have not been processed for

their roles in dictatorship crimes, whilst others continue to wield influence

in Chile’s legal and political hierarchy.

‘La danza de los cuervos’ is both an indispensable read and a significant

contribution to Chile’s struggle against oblivion and impunity. The

exploitation of humanity decreed by Pinochet and Contreras is vividly depicted

without committing error of shifting the focus from the detenidos

desaparecidos. Rebolledo weaves his discourse out of a sequence of betrayals

within diverse factions in Chile, compellingly bequeathing the memory of the desaparecidos

to a country split between loyalty to the dictator’s manipulation and the

masses clamouring for an integral part of their narrative which wallowed in

oblivion for decades.